The Nation’s Health During Martial Law

Behind a government that proudly showed the world that its nation was strong and seemingly invincible, is a national health crisis that left future generations to search for a cure. Throughout the years of the Marcos regime, the health of the Philippines was in constant deterioration. The continuous neglect of health care resulted in dangerously alarming statistics and a national health crisis that seemed insoluble. Although there were numerous health facilities that were constructed (some of which remain functional until today), the services that were offered proved to only be lackluster.

Critical information that had the capability to save lives was hidden and manipulated, and several cases of maltreatment of patients by using inadequate remedies and equipment were reported. But perhaps nothing can be worse than the countless accounts of tortures and beatings that took place during that time, some of which had participation from medical personnel. The infrastructures and facilities were there, but the support for the patients was limited and the crisis only worsened. It was definitely a critical time in national health that the government chose to turn its backs on and look the other way, leaving millions desperately seeking basic health care treatment just so they can live another day.

Shot in the Head and Left for Dead

Hundreds of civilians each year were caught in a crossfire during Martial Law, and Antonio Mabayag and his son were one of them. An instance that no one would ever wish to experience, let alone with their own child. In his local barrio in Negros, Mabayag, along with his 8-year-old son were shot by soldiers who were pursuing communist rebels.

His son was killed in the crossfire and Mabayag himself was shot in the head. Though he was left for dead, Mabayag still managed to survive. After it was discovered that he was still alive, Mabayag was rushed to a hospital in Bacolod City where he was admitted.

His case is a prime example of the injustice in the healthcare system and the maltreatment of patients during that time. During the several weeks that Mabayag stayed in the hospital, he only received one examination from a government physician and one blood transfusion, both of which were done on his first two days. His second scheduled blood transfusion was forgotten by the hospital staff and was only remembered a few weeks after when a nurse discovered that the bag of blood that was allocated to Mabayag was already expired. A patient that was shot in the head, fighting for his life, was only treated once in his whole admission to the hospital. After the blatant disregard for Mabayag, he was eventually discharged and transferred to his village where he was to be cared for. Antonio Mabayag’s experience as a medical patient during Martial Law is an example of the inadequacies of the services in hospitals with their lack of attention and sense of urgency, considering that Mabayag was already in critical condition.

Torture and Hostilities with Medical Participation

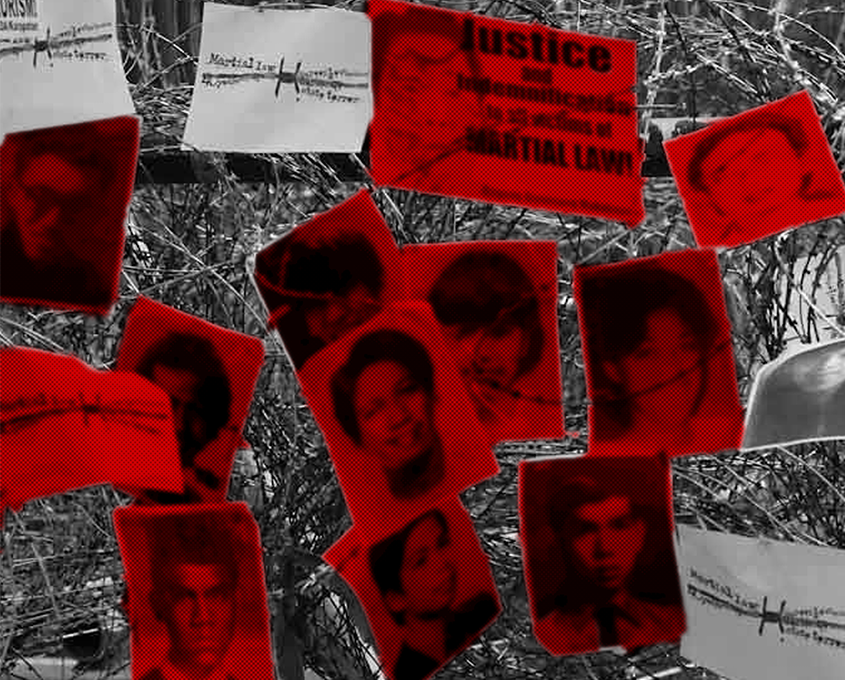

Even though the Philippines has little evidence of the systematic transgressions done by the military that was in cooperation with medical personnel during Martial Law, human rights groups have now possessed testimonials, specifically from former detainees experiencing torture and hostility from prison medical personnel.

In one situation in Northern Luzon, after the arrest of a psychology student in 1983, a Philippine Constabulary Intelligence officer punched him several times in the neck and stomach and even banged his head on the wall at one time. After being examined, the prison doctor made him sign a medical certificate stating that he had not experienced ill-treatment, despite having bruises on his head and stomach. When he was released, the detainee then filed a court complaint of the atrocities that he had suffered but was later dismissed on the basis of the medical certificate.

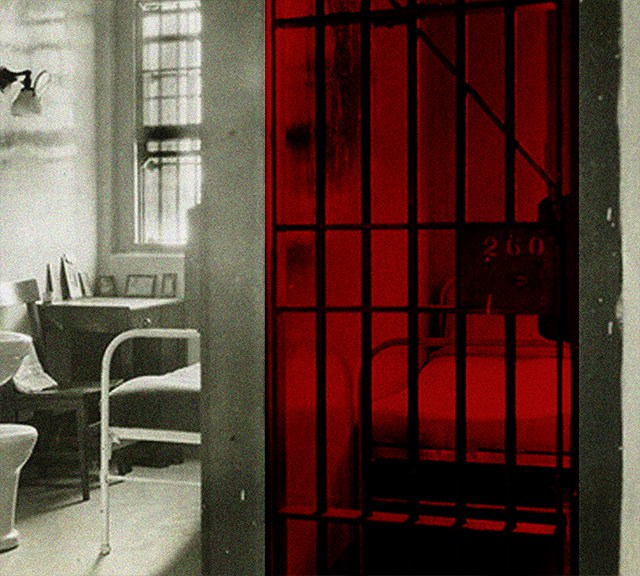

In another instance, Vicente Ladlad, a detainee in 1983 who was held in solitary confinement for two years and nine months, stated that throughout that time, the solitary confinement guards never allowed him to sleep. They even threatened to salvage (extrajudicial execution) Ladlad as he failed to cooperate with his interrogators. Ladlad also stated that on the sixth day of his interrogation, despite running a fever, the doctor told the interrogator: “Kaya pa niya”.

In another case, a couple who had serious psychiatric conditions days after their arrest were denied access to be examined by medical professionals. When they were released, they were prescribed tranquilizers, despite never receiving any psychiatric evaluation or examination from any medical professional.

Though the cases mentioned above still remain unclear since neither the PMA nor the PCHR has investigated the treatment of the detainees, it would still be a clear presentation of the hostilities that took place during Martial Law, as well as the disregard for the rights of the patients especially those who were in prison.

The Health Situation after Martial Law

The government that followed Martial Law was left with a nation that was in critical condition. Based on surveys and studies by private foundations, international aid agencies, and Philippine government figures, 79% of all preschool children suffer from malnutrition in the Philippines, which prompted the use of the Nutribun bread in feeding programs for children.

Although the Nutribun was glorified as a means by Marcos to combat hunger on a national scale, it only further revealed the nutritional crisis that was caused by his administration. The Nutribun was a product of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and was used to target malnutrition child populations.

However, during the “Great Flood” in 1972, the millions of Nutribun bags that were donated were stamped with the slogan “Courtesy of Imelda Marcos – Tulungan Project”, a complete credit grab from the USAID and their program. What was supposed to be an afternoon snack for kids became a method of promoting the Marcos administration through disaster feeding.

Out of 1000 Filipino babies, 44 of every 1000 Filipino babies die before the age of one primarily because of deliveries that were done by unskilled individuals in unsanitary conditions. Measles killed thousands of children each month with the country lacking the vaccines for large rural populations, and the Philippines had the highest incidence of whooping cough, rabies, and diphtheria in the world, and the largest number of schistosomiasis, tuberculosis, and polio cases in the western pacific.

In addition, A study from Asian Development Bank showed that Filipinos had the lowest average food intake in Asia. This would be the result of many cases of famine that the country experienced, most notably the “Negros Famine” which involved the bankruptcy and loss of livelihood for sugarcane farmers in the Negros Province in the 1980s. The Philippines also has the third-highest number of blind people in the world with most resulting from a lack of vitamin A. 80% of the population suffer from diseases with 43% having been avoided only if the patients received the most basic medical care, with 62 of every 100 Filipinos died each year without receiving any medical attention. Of the nation’s 1600 municipal districts, more than half do not have health centers or hospitals, with regional, provincial, and district hospitals being poorly equipped to the point where patients were better off being treated elsewhere. With all these facts and numbers, it’s quite clear that the Philippines after Martial Law was in one of its worst periods in terms of national health, a problem that the future leaders had to face.

It is evident that Martial Law left the Philippines in grave conditions. The case of Antonio Mabayag showed the ignorance and inadequacy of the healthcare system that was supposed to be responsible for a patient that lost his son and was almost killed in a crossfire. The participation of medical professionals in the hostilities and maltreatment of detainees gave a sight of how truly corrupt and abusive authorities were, completely ignoring the ‘human’ in human beings. Lastly, the health problems that were faced by the government that succeeded the Marcos Regime left the country with a disease in national proportions, one that seemed impossible to heal.